Tan Yean San

National University of Singapore

Faculty of Law

As the Malay adage goes, “Satu kapal dua nakhoda.” A ship cannot have two captains. When state and federal leaders do not meet eye to eye, whose instruction should the people heed? This was the dilemma confronting Malaysians in early May, when state and federal authorities could not agree on lifting the Movement Control Order (“MCO”).

The Background to Liberalization

On 18 March 2020, the Malaysian government implemented a nationwide lockdown in the form of the MCO. The MCO was subsequently extended thrice more before it was replaced by the first phase of liberalization – the Conditional Movement Control Order (“CMCO”) – on 4th May 2020. Intended to “revitalize or restart the economy in an orderly and controlled manner”, the CMCO would, in principle, lift most of the restrictions surrounding commercial activity. Small, local businesses could reopen while industrial enterprises could resume. Dining-in and recreational activities were henceforth legal so long as they did not attract a crowd. Interstate travel was permitted for work purposes, whereas under its predecessor, the MCO, interstate travel and public gatherings were banned. Residents were only allowed to travel for the purpose of fulfilling basic needs or seeking essential services, which were prescribed in a closed list under Section 3(2) and the Schedule of the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases (Measures within Infected Local Areas) (No. 4) Regulations 2020.

Malaysian Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin had made the decision to implement the CMCO as the financial toll of a prolonged lockdown had become too heavy to bear. The government reported whopping daily national income losses of RM 2.4 billion. If the MCO were to continue until June, the country would be RM 98 billion in the red. Furthermore, the unemployment rate in Malaysia as of April 2020 had already hit an unprecedented high of 5%, a spike of 48.8% from last year’s numbers. It was unsurprising that the CMCO received popular support from industry associations.

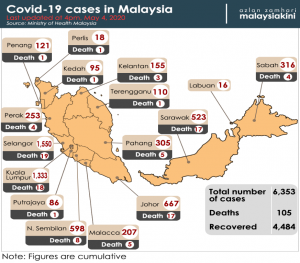

However, the federal government’s sudden pivot to resuming economic activities caught many Malaysians off guard. The CMCO was expected to commence a mere 3 days later after its public reveal. Many initially thought the move to be unwise – a “premature relaxation [that] would only result in unending queues to the cemetery”. Their worries were not unfounded. Malaysia saw 122 positive cases on the 3rd of May alone. Over 450,000 Malaysians signed a petition objecting to the CMCO.

Figure 1: The Covid-19 situation in Malaysia as of 3 May 2020.

The Defiance against Liberalization

More critically, the CMCO received a heated backlash from the state governments. Within 2 days of the Labour Day announcement, 9 out of 13 states rejected following the new law. The state leaders of Sabah, Sarawak, Penang, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Kelantan, Pahang, Kedah and Melaka were reportedly upset at the short 3-day notice. The new law had prescribed only generic standard operating procedures (SOPs). This effectively left the state governments to do the heavy lifting – communicating the new guidelines to local businesses, drawing up assessment rubrics and determining the enforcement logistics. These tasks were part and parcel of state administration, which is under the jurisdiction of state governments. In ordinary times, the local governments were responsible for issuing licenses to local traders. Within the Covid-19 context, the state security working committees (headed by the respective Chief Ministers) were responsible for devising the applicable SOPs and answering concerns from the local population. The state government could prevent businesses from operating if they contravened existing laws or social-distancing SOPs.

The other refrain was that the federal government’s concerns were not attuned to the people’s priorities. Many were still concerned about the Covid-19 spread. State leaders lamented the federal government’s hastiness; they refused to restore the economy “at the expense of people’s lives”.

The defiance manifested in two ways. The more conspicuous act of rebellion was to delay the commencement of the CMCO altogether. In Sabah, Sarawak, Penang and Pahang, the resumption of business activity was postponed by a period of 4 days to slightly over a week. Penang came up with its own CMCO plan altogether. This earned a great deal of hostility from the incumbent government. Minister for Trade and Industry Azmin Ali warned the detractors of the prospect of lawsuits from ‘various players’, in a speech widely seen to be a thinly-veiled threat. Even the monarchy got involved. The Sultan of Selangor issued a decree to implement CMCO in the state, effectively overriding the Selangor Chief Minister’s reluctance to lift the MCO in the state.

Figure 2: “Poor Mak Cik KIah in Sungai Tua has to wait for more than a week to get permission to eat in a restaurant” – Minister Azmin Ali, the previous Selangor Menteri Besar takes a jibe at his successor Amirudin Shari’s decision to delay resumption of dine-in services.

The alternative way to circumvent the CMCO was much more covert. Nearly all 13 states opted to modify the list of economic sectors that could reopen. Many states such as Perak, Selangor, Kelantan and Negeri Sembilan, still prohibited dine-in services. In Melaka, this rule was only relaxed from 5 June onwards. Liberalization measures only achieved uniformity across the states when the CMCO was replaced by the Recovery Movement Control Order on 10th June.

Was the defiance legal?

The CMCO was set out by the federal authorities in the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases (Measures within Infected Local Areas) (No. 5) Regulations 2020 (“No. 5 Regulations”). The No. 5 Regulations removed the legal basis for state authorities to continue enforcing the MCO as it superseded the No. 4 Regulations, which was gazetted on 29th April 2020. Section 13 of the No. 5 Regulations expressly revoked the operation of the No. 4 Regulations as of 3 May 2020.

The No. 5 Regulations differed significantly from the No. 4 Regulations. Section 3 of the No. 4 Regulations had imposed a blanket ban on all forms of travel subject to 15 exceptions (‘essential services’) in its Schedule. Even when the exceptions applied, the average resident could not travel beyond a 10km radius of his home. In short, economic activity came to a standstill since businesses offering non-essential products and services could not operate. Workers could not travel to worksites and offices and there was simply no customer traffic.

The No. 5 Regulations did the opposite. It lifted the blanket ban on travel and subjected residents to a list of 13 prohibited activities in its Schedule. It was an offence to engage in prohibited activities such as entertainment, religious and business activities that would cause a crowd to gather or were organized in public spaces outside of its premises. Tourism activities, barbershop and beautician operations, cinemas and the marketing of financial services in public compounds were also banned pursuant to Section 3 of the No. 5 Regulations. Section 5(1) allowed inter-state travel for work purposes to resume. Almost all economic sectors could restart subject to the caveat that they had crowd control measures on their premises.

Article 75 of the Malaysian Federal Constitution states that federal law takes precedence over state law where federal and state jurisdictions clash on specific issues. Furthermore, Article 81 decrees that states cannot “impede or prejudice the exercise of the executive authority of the Federation”. In further delimiting the scope of activities allowed to resume or even delaying the CMCO, state governments may have ran afoul of the Federal Constitution. The real question is whether the decisions of the state authorities have thwarted federal intention behind the CMCO.

There is some support for finding that the state governments had clearly acted against Article 81. The federal government had intended the (No. 5) Regulations to be implemented with immediate effect on 4th May. Yet, not only did a few states delay commencing the CMCO later than the prescribed date, almost all 13 states took the liberty to alter the list of prohibited activities under the Schedule as they saw fit. Their actions are clearly incongruent with federal intention behind the (No. 5) Regulations. The federal government’s utmost priority was to stem the snowball effect of daily income loss. Every day that the CMCO was delayed translated to another day’s loss of revenue for local businesses and another dangerous step towards rising unemployment. By delaying the lifting of the MCO and further shrinking the list of permitted economic activities, the states were effectively contributing to the mounting national debt. It is difficult to see how their actions did not undermine federal intention.

So why were the state governments let off?

The federal government’s intentions must be viewed against the political context back in May. It was highly likely that, given the practical difficulties and time constraints involved in implementing the CMCO, state governments would require more than a three-day notice period to get their affairs in order. Hence, the delay in implementation and the culling of business operations at risky areas such as wet markets. The state governments’ decisions can still be construed as a genuine attempt to effect the CMCO by taking more precautionary measures. The other likelihood could be that the federal government had already foreseen that there would be resistance to lifting the lockdown. Their ultimate target could have been to reopen the economy fully by June 2020. Hence, the state governments’ non-compliance was tolerated.

The Aftermath

On one hand, it seems that this dispute may have exacerbated the trust deficit in state-federal relations. Back in early May, only 5 states (including Johor) remained under the Opposition’s control, yet an overwhelming majority of the states openly rebuked a federal directive. Considering Malaysia’s political crisis earlier in March that witnessed an incredible surge in party-hopping, the defiance was, realistically, an act of self-preservation. The political crisis has proven that the support of political parties could be highly unreliable. Given the unfavourable initial public reception to the CMCO, state leaders would rather implement the CMCO gradually than risk incurring public ire. The silver lining is that the state and federal governments were at least willing to compromise. Malaysia ultimately adopted a unified approach towards the next phase of liberalization – the Recovery Movement Control Order. The tension in the state-federal relationship has not reached a degree that prevents cooperation.

On the other hand, it does seem that the state governments’ gambit has paid off. They have inspired greater public confidence in local authorities. Studies have shown that public trust is essential for the success of government policies to stem the spread of Covid-19. Many people were still afraid of contracting Covid-19 in early May; there was much support for extending the MCO beyond 28 April. The state governments’ refusal to transition into the CMCO at the expense of their people’s health was precisely the reassurance that Malaysians needed – that the government cared for their safety, and their voices were being heard.