ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE & ROBOTS - May 2024

An Exploration of AI Evaluation Regimes in Singapore and Worldwide (Part 1)

By Dr Stanley Lai, SC, David Lim, Linda Shi, and Justin Tay (Allen & Gledhill LLP)

I. Introduction

The transformative potential of artificial intelligence (“AI”) needs no introduction. Many organisations are increasingly exploring the possibility of implementing generative AI in their systems. IBM’s Global AI Adoption Index 2023 reports that about 42% of enterprise-scale companies are actively deploying AI in their business and another 40% are exploring doing so.[1]

It has also become manifestly apparent that deploying AI comes with several attendant risks, especially since the technology is new and rapidly developing. Indeed, the public is becoming increasingly concerned over the safety and societal impact of AI. Global public trust in AI companies dropped to 53% in March 2024, down from 61% in 2019.[2] It is therefore no surprise that governments and international organisations such as the OECD have identified that public trust is vital to the continued adoption of AI technology.[3] Evaluation of AI models is a necessary process for organizations and individuals to be apprised of risks and other adverse consequences that may follow from the use of AI models.

To manage these risks, governments have acknowledged that establishing AI evaluation models will help ensure that AI is developed with commensurate accountability, so as to foster public trust and the continued use of AI technologies. To this end, at the AI Safety Summit held in the UK in November 2023, 29 countries, including Singapore, signed the “Bletchley Declaration”, agreeing on a need to establish “appropriate evaluation metrics” and “tools for safety testing” regarding advanced AI.[4] Many governments have also published guidance and legislation on evaluating AI models.

Singapore is no exception and since 2019 has produced one of the world’s most developed and technically detailed AI evaluation regimes. The regime is growing fast, with two significant advances made in March. On 1 March 2024 the Personal Data Protection Commission (“PDPC”) published Advisory Guidelines on Use of Personal Data in AI Recommendation and Decision Systems (“PDPC Guidelines”);[5] and on 15 March 2024 a consultation closed on the Proposed Model AI Governance Framework for Generative AI (“Proposed Model Framework”).[6]

Given these recent developments, the first part of this two-part article on AI evaluation regimes will review Singapore’s complex AI evaluation regime, setting out the key sources, principles, and approaches, as well as likely future developments. The second part will review AI evaluation regimes in other jurisdictions and international organisations, setting out their similarities and differences in comparison and contrast to the Singapore regime.

II. The Singapore AI Evaluation Regime

Singapore’s AI governance regime has two distinctive characteristics. First, it is entirely advisory and non-binding, taking the form of guidelines and frameworks rather than of legislation. Second, it has separate rules for generative AI versus for “traditional” AI. This article will first address evaluation of the traditional AI regime, followed by the generative AI regime. Singapore has at present opted for a framework/guidance-based, non-statutory approach to evaluating AI.

A. The Singapore Evaluation Regime for Traditional AI

Singapore’s traditional AI evaluation regime comprises the AI Verify Minimum Viable Product (“MVP”), the world’s first framework/toolkit for testing AI governance, as well as the PDPC Guidelines. The regime applies to traditional AI only, since the MVP and the PDPC Guidelines do not apply to generative AI.[7]

Singapore’s traditional AI evaluation regime began with the Model Artificial Intelligence Governance Framework (first edition 23 January 2019, second edition 21 January 2020[8]). This used testing as an example of good AI governance but did not provide any framework/toolkit.

Thereafter, Singapore’s traditional AI evaluation regime was developed with the launch of the MVP by the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) and the PDPC on 25 May 2022. The MVP is a voluntary self-assessment framework, which aims to let industry players demonstrate to stakeholders that they have implemented responsible AI through an objectively verifiable combination of technical tests and process checks.[9] Whilst the regime is voluntary, IMDA and PDPC have highlighted that participating organisations could enjoy benefits such as increased stakeholder trust, the ability to join an AI testing community to network and collaborate, and the opportunity to help IMDA shape the regime through feedback.[10] The MVP had numerous notable initial adopters including Microsoft, Singapore Airlines, and Standard Chartered Bank.[11]

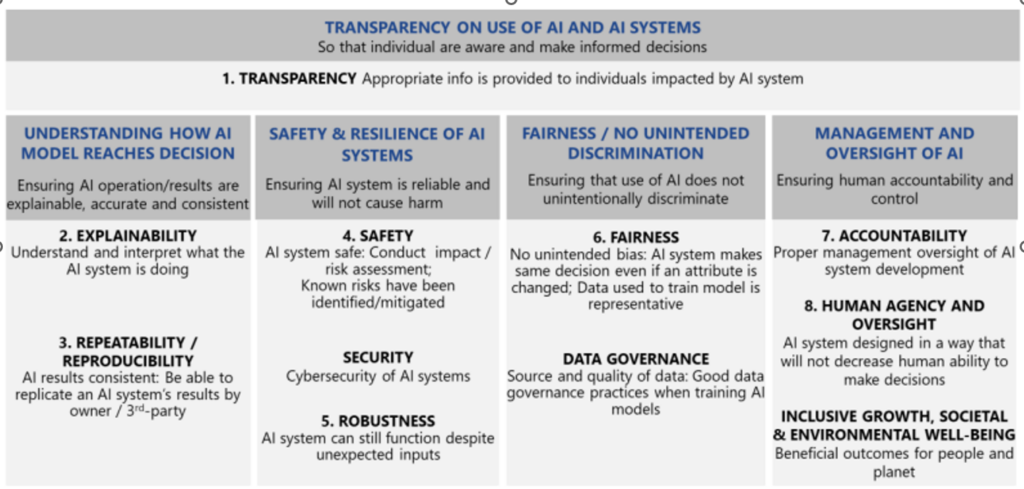

The MVP contains an initial set of eight principles against which organisations can test their compliance. These broadly include ensuring that: AI systems and use of AI are transparent; AI operations are repeatable and explainable; AI systems are safe and reliable; AI systems are fair and do not unintentionally discriminate; and there is human accountability and oversight.[12] The full list of principles is reproduced below:

Figure 1: The MVP’s list of principles[13]

The MVP Invitation to Pilot introduced a twofold approach to evaluation. First, a Testing Framework specifies the testable criteria relevant to the abovementioned AI ethics principles. Second, a Toolkit is used to execute technical tests and record process checks described in the Testing Framework.[14] To elaborate:

- The Testing Framework comprises definitions of the AI ethics principles, prescribed testable criteria, actionable steps for testing, measurable metrics, and thresholds for acceptable values or benchmarks for the selected metrics.[15]

- By contrast, the Toolkit is used to execute technical tests and record process checks described in the Testing Framework. In short, the Toolkit aims to provide a “one-stop” suite of open-source technical testing tools in a “Docker” container.[16] The Toolkit also guides users step-by-step through the testing process and helps users interpret the results of the tests. Under the present framework, the Toolkit provides process checks for all eight principles, but provides technical tests for the principles of fairness, explainability, and robustness only.

The MVP approach remains the cornerstone of Singapore’s traditional AI evaluation regime and the IMDA plans to release an updated AI Governance Testing Framework and Toolkit Version at the end of the pilot phase. To increase support for the MVP, the IMDA announced on 7 June 2023 the launch of its not-for-profit subsidiary the AI Verify Foundation, which, in addition to being the hub for the MVP, is intended to harness the collective power and contributions of the global open-source community to develop responsible AI.[17]

On the other hand, the PDPC Guidelines, published on 1 March 2024, constitute the most recent development in Singapore’s traditional AI evaluation regime. The Guidelines apply where the design or deployment of AI in recommendation and decision systems (a subset of traditional AI) involves the use of personal data in scenarios governed by the Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (“PDPA”). The PDPC Guidelines provide clarity on how the PDPA applies when organisations use personal data to develop and train AI, and sets baseline guidance and best practices which will help organisations be transparent about whether and how their AI systems use personal data to make recommendations, predictions, or decisions.

The PDPC Guidelines also explain how organisations can comply with the PDPA’s Consent and Notification Obligations and Accountability Obligation. The PDPC Guidelines also explain how organisations might rely on the Business Improvement Exception and/or the Research Exception at three stages of AI system implementation: (1) development, testing, and monitoring; (2) deployment from business to consumer; and (3) procurement from business to business.

To elaborate, personal data can be used without user consent by relying on an exception in the PDPA. Broadly, the Business Improvement Exception can apply when businesses are developing AI systems to enhance an existing product or service (e.g. developing an AI system to provide personalised product recommendations for consumers), including through bias assessments (i.e. assessing the bias of a training dataset so that an AI system using it can be di-biased).[18] Conversely, the Research Exception can apply when organisations conduct commercial research to develop AI systems that have public benefit, e.g. for precision medicine.

In terms of data protection considerations, the PDPC Guidelines emphasise that organisations should adhere to “data minimisation”, i.e. using identifiable personal data as little as possible.[19] Organisations are also reminded to carefully consider appropriate security measures (based on the types of disclosure/theft risks that the personal data would be subject to, and the sensitivity and volume of the personal data) and conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment.[20]

Finally, the PDPC Guidelines reiterate that organisations should establish personal data policies and practices and keep them updated.[21] Policies should cover issues such as when model training should be conducted using anonymised or pseudonymised data, and when it is permissible to use identifiable personal data. The Guidelines also clarify that technical tools and process checks under the MVP can be used to validate the performance of AI systems.[22]

B. The Singapore Evaluation Regime for Generative AI

Singapore’s generative AI evaluation regime has emerged more recently, following just months after the momentous launch of ChatGPT in late 2022, which caused the nascent but fast-developing generative AI technology to explode into public consciousness. On 5 June 2023, the AI Verify Foundation published the discussion paper titled “Generative AI: Implications for Trust and Governance” (“Discussion Paper”), which recommends a “practical, risk-based and accretive approach” to generative AI evaluation, focusing on six key dimensions to enhance trust and safety in generative AI: accountability in the development lifecycle; data use in generative AI training; model development and deployment (including the development of evaluation framework and tools); independent third-party evaluation and assurance; safety and alignment research; and using generative AI to achieve public good.[23] The Discussion Paper also urged greater global collaboration towards a common platform and governance framework for generative AI.[24]

The next significant milestone in the generative AI evaluation regime came on 31 October 2023, when the IMDA and the AI Verify Foundation published the draft paper “Cataloguing LLM Evaluations” (“Evaluation Catalogue”)[25] along with a Generative AI Evaluation Sandbox (“Sandbox”).[26] (This is distinct from the generative AI sandbox for SMEs launched on 7 February 2024,[27] which helps SMEs incorporate generative AI into their business and does not concern evaluation.)

The Evaluation Catalogue focuses on the third dimension of the Discussion Paper (i.e. model development and deployment) and sets out a comprehensive overview of the LLM evaluation and testing landscape. Interestingly, the Evaluation Catalogue also builds upon the MVP principles, which it considers to be instructive (though from a distinct regime), and explains why the three principles of robustness, fairness, and data governance apply to LLMs.[28] Finally, the Evaluation Catalogue sets out baseline standards for pre-deployment LLM evaluation, in accordance with these three principles.

Notably, the Evaluation Catalogue arranges LLM evaluation methods into five broad categories based on what they evaluate: [29]

- general capabilities (e.g. natural language understanding);

- domain-specific capabilities (in law, medicine, and finance);

- safety and trustworthiness (e.g. toxicity generation and bias);

- extreme risks (dangerous capabilities and alignment risks); and

- undesirable use cases (e.g. misinformation and adult content).

Like the MVP’s eight principles for traditional AI, this grouping demonstrates that Singapore’s AI evaluation regime has a broad scope. It also demonstrates the heightened ethical concerns attaching to generative AI (safety, extreme risks, and undesirable use cases). However, the testing framework is still focused on verification and trust rather than imposing ethical standards.

The Evaluation Catalogue then proposes a testable baseline for LLMs based on adherence to five attributes (which are based on the three principles mentioned above): robustness, factuality, bias, toxicity generation, and data governance.[30] Like the MVP, for each of these principles the Evaluation Catalogue recommends both benchmarks and evaluation frameworks (all open-source). For example, for factuality the benchmark is TruthfulQA (used by Meta, OpenAI, and Anthropic) and there are three possible evaluation frameworks (HELM, BigBench, and Eleuther Evaluation Harness). There is also a greater focus on red teaming (a form of adversarial testing which involves authorising ethical hackers to attack an organisation’s systems, simulating a real attack).[31] The Evaluation Catalogue gives three factors which organisations should consider when using the proposed baseline:[32]

- Testing approaches should be contextually attuned, e.g. bias testing should use benchmarks/frameworks attuned to the LLM’s user demographic.

- Where an LLM is fine-tuned before deployment, repeat evaluations may be warranted.

- Additional evaluations may be warranted for “frontier” model risks, e.g. dangerous capabilities and high risk of losing human control. (This mirrors the “extreme risks” section of the catalogue.)

The Evaluation Catalogue also suggests future directions for generative AI evaluation. Human scoring is “more nuanced” and the “gold standard”, but it has disadvantages like subjectivity and fatigue, and using LLMs to conduct AI evaluations is 22 times cheaper and 129 times faster.[33] Therefore, it seems likely that Singapore’s AI evaluation regime will increasingly encourage “LLM-to-LLM” evaluation. The Evaluation Catalogue also highlights the issue of a lack of standardisation in AI evaluation.[34]

Meanwhile, the Sandbox is anchored on the Evaluation Catalogue and aims to bring industry players worldwide together to build a body of common evaluation tools and develop new benchmarks and tests. It also lets industry players interact with government: for example, Anthropic has given the IMDA access to some of its models to let the IMDA advance red teaming techniques.[35] Other participants in the Sandbox include key model developers such as Google, Microsoft, and Stability AI.

The most recent development in the generative AI evaluation regime is the closing of a consultation on the Proposed Model Framework.[36] The IMDA and the AI Verify Foundation published the Proposed Model Framework on 16 January 2024; the consultation closed on 15 March 2024 and the IMDA intends to finalise the proposed framework by mid-2024.[37] This would be the third edition of a Model AI Framework released in Singapore, and unlike the previous two it would concern generative AI.

The Proposed Model Framework builds on the policy ideas highlighted in the Discussion Paper, and, in line with the Evaluation Catalogue, it maintains the approach of setting “baseline safety practices” for generative AI evaluation.[38] It also introduces new concerns, such as incident reporting and security.[39] Its specific suggestions include adding standardised “food labels” to data disclosures to indicate to downstream users information such as the data used and safety measures implemented.[40] It envisages an accreditation mechanism for AI testers.[41] While it does not introduce ethics into the AI evaluation regime, it recommends increased investment in AI safety R&D and “global cooperation among AI safety R&D institutes”.[42] Industry players should watch for how the IMDA responds to the consultation results.

III. Concluding Comments

The two main features of the Singapore AI evaluation regime are its non-binding, advisory nature, and its split between traditional and generative AI. However, as seen above, it has many other distinctive characteristics. The regime is well-developed and precise, with a catalogue of testing techniques, and recommended open-source benchmarks and testing frameworks. Although advisory, the regime promises benefits like increased stakeholder trust and has had significant adopters from the start. Evaluation methods are split between process checks and technical tests, for traditional AI. The regime is becoming increasingly nuanced: for example, the PDPC Guidelines have introduced new considerations regarding personal data use in model testing. Organisations have numerous sets of principles and categories to refer to in different contexts, e.g. the eight MVP principles for traditional AI and the five testing categories in the Evaluation Catalogue. Despite generative AI being a “hot topic”, the traditional AI regime is still advancing, for example with the PDPC Guidelines. Increasing concern is evident with AI policy issues like extreme risks, but evaluations remain value-neutral, focused not on compliance or information sharing with government but on promoting quality and trustworthiness in AI models.

Lastly, Singapore has expressed a desire to foster an international AI evaluation community and harmonise AI evaluation approaches. The next part of this two-part article will compare the Singapore approach with the approaches of other countries and international organisations.

AUTHOR INFORMATION:

Dr Stanley Lai, SC is a Partner at Allen & Gledhill, where he is also the Head of the Intellectual Property Practice and Co-Head of the Cybersecurity & Data Protection Practice.

Email: stanley.lai@agasia.law

David Lim is a Senior Associate in the Intellectual Property Practice of Allen & Gledhill.

Email: david.lim@agasia.law

Justin Tay is an Associate in the Intellectual Property Practice of Allen & Gledhill.

Email: justin.tay@agasia.law

* The authors would like to thank Joseph Court, a Visiting Practice Trainee at Allen & Gledhill, for his assistance in the production of this article.

REFERENCES

[1] https://newsroom.ibm.com/2024-01-10-Data-Suggests-Growth-in-Enterprise-Adoption-of-AI-is-Due-to-Widespread-Deployment-by-Early-Adopters (this and all other URLs accessed 11 April 2024).

[2] https://www.axios.com/2024/03/05/ai-trust-problem-edelman.

[3] https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2023/trust-in-ai-global-insights-2023.pdf, endnote 12.

[4] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-safety-summit-2023-the-bletchley-declaration/the-bletchley-declaration-by-countries-attending-the-ai-safety-summit-1-2-november-2023.

[5] https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/-/media/files/pdpc/pdf-files/advisory-guidelines/advisory-guidelines-on-the-use-of-personal-data-in-ai-recommendation-and-decision-systems.pdf.

[6] https://aiverifyfoundation.sg/downloads/Proposed_MGF_Gen_AI_2024.pdf.

[7] The AI Verify Foundation’s website https://aiverifyfoundation.sg/what-is-ai-verify/, and a post from the PDPC https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/help-and-resources/2020/01/model-ai-governance-framework, both specify that the MVP “cannot test generative AI/LLMs”. Separately, in a speech by Communications and Information Minister Josephine Teo on the day the PDPC Guidelines were launched https://www.mci.gov.sg/media-centre/speeches/minister-committee-of-supply-debate-2024/#:~:text=Following%20extensive%20consultations%20with%20stakeholders,to%20train%20generative%20AI%20systems, she indicated that PDPC will next consider giving separate guidelines on the use of personal data to train generative AI systems (all links accessed 11 April 2024).

[8] https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/-/media/files/pdpc/pdf-files/resource-for-organisation/ai/sgmodelaigovframework2.pdf.

[9] https://file.go.gov.sg/aiverify.pdf.

[10] Above note 9, para 6.

[11] https://www.imda.gov.sg/-/media/imda/files/news-and-events/media-room/media-releases/2022/05/annex-a---ai-verify-quotes-from-industry-and-partners.pdf.

[12] Above note 9, para 10.

[13] Above note 9, para 10 (Figure 1).

[14] Above note 9, para 15.

[15] Above note 9, para 16.

[16] Above note 9, paras 17-18.

[17] https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/news-and-events/announcements/2023/06/launch-of-ai-verify-foundation-to-shape-the-future-of-ai-standards-through-collaboration.

[18] Above note 5, para 5.1 to 5.9.

[19] Above note 5, para 7.1.

[20] Above note 5, paras 7.3-7.4.

[21] Above note 5, para 7.7.

[22] Above note 5, para 10.10.

[23] https://aiverifyfoundation.sg/downloads/Discussion_Paper.pdf, p. 16.

[24] Above note 23, p. 27.

[25] https://aiverifyfoundation.sg/downloads/Cataloguing_LLM_Evaluations.pdf.

[26] https://www.imda.gov.sg/resources/press-releases-factsheets-and-speeches/press-releases/2023/generative-ai-evaluation-sandbox.

[27] https://www.imda.gov.sg/resources/press-releases-factsheets-and-speeches/press-releases/2024/sg-first-genai-sandbox-for-smes.

[28] Above note 25, paras 42-45.

[29] Above note 25, para 12.

[30] Above note 25, para 46.

[31] Above note 25, para 14.

[32] Above note 25, paras 48-52.

[33] Above note 25, paras 30-31.

[34] Above note 25, para 24.

[35] Above note 26.

[36] https://aiverifyfoundation.sg/downloads/Proposed_MGF_Gen_AI_2024.pdf.

[37] https://www.imda.gov.sg/resources/press-releases-factsheets-and-speeches/press-releases/2024/public-consult-model-ai-governance-framework-genai.

[38] Above note 36, p. 10.

[39] Above note 36, p. 4.

[40] Above note 36, pp. 10-11.

[41] Above note 36, p. 15.

[42] Above note 36, p.4.