Media - News

- Media

- CLT Singapore Symposium for Legal Theory with Prof. Paul Halliday & Dr. Sabarish Suresh on 10-11 March 2025

CLT Singapore Symposium for Legal Theory with Prof. Paul Halliday & Dr. Sabarish Suresh on 10-11 March 2025

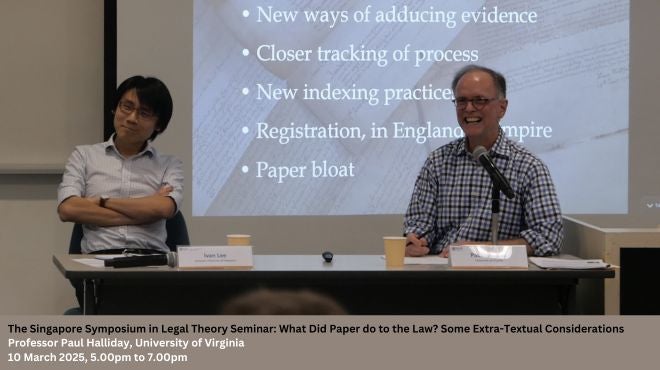

In the lecture “The Stuff of Law: Materiality and Legal Form” on the 10th March by Professor Paul Halliday, the materiality of legal practice was examined as a defining force in shaping both the nature and function of law. Rather than treating law as an abstract system, this project investigates how its tangible forms—litigation spaces, archival practices, and mediums of record-keeping—actively shape legal outcomes and possibilities. For instance, the transition from parchment to paper was not merely a shift in material but a transformation in how law was recorded, interpreted, and applied across different jurisdictions from the fifteenth to nineteenth centuries. By tracing developments such as the growing reliance on affidavits, the procedural formalization of printed legal forms, and the adoption of the codex for indexing, Professor Halliday illustrated how the physicality of law is not incidental but constitutive of legal meaning itself. Ultimately, the study of law’s material forms reveals that legal change is not only a matter of evolving doctrine but also of shifting media, storage, and spatial practices that determine what can be known, argued, and enforced as law.

In the lecture “Partition’s Lingering Shadow: Repression and Constitutional Memory” on 11th March, Dr Subarish showed how partition emerges not as a historical backdrop but as the foundational rupture that shaped the making of the Constitution—a trauma largely ignored in conventional legal scholarship. By drawing on archival materials, including colonial records, Constituent Assembly debates, and private correspondence, Dr Subarish reconstructs how the violent scission of partition directly influenced the formulation of Article 343, the language provision of the Indian Constitution. Yet, despite its structural significance, partition remains a repressed presence in legal discourse, its affective weight systematically denied by both historical narratives and judicial interpretations. Through an analysis of key Supreme Court and High Court rulings on language policy, Dr Subraish argues that the judiciary has actively suppressed partition’s legacy, refusing to engage with its lingering impact on legal and political identity. Using psychoanalytic theory, Dr Subarish positions partition as the ‘repressed kernel’ of Indian constitutionalism—an originary violence that, having been negated, resurfaces in contemporary India in dislocated and distorted forms. In doing so, it calls for a reckoning with the Constitution’s unspoken histories and the ways in which law remains haunted by the very ruptures it seeks to forget.