Tan Yean San

National University of Singapore

Faculty of Law

Enforcing compliance with social distancing laws has been challenging to any government administration. This is primarily attributed to their intrusiveness and the heavy demands imposed on government resources for enforcement. The problem is especially pronounced in jurisdictions where there is weak public confidence in the administration. In Indonesia, only half of the population expressed faith in the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Indonesia’s Covid-19 strategy has, therefore, looked beyond formal enforcement and relied significantly on community policing, notably social sanctions and other creative ground-up efforts by local communities to enforce social-distancing regulations.

Social Sanctions

The formal sanctions prescribed by Article 93 of Law No. 6 of 2018 on Quarantines (the legal basis for Indonesia’s partial lockdown) include a year’s imprisonment and a maximum fine of Rp. 100,000,000 (USD6,812). In practice, however, these criminal sanctions have rarely been meted. Instead, authorities have leaned towards issuing social sanctions, which were deemed to have equally strong deterrence effects in the form of public shaming.

Figure 1: A PSBB violator sweeping the streets in Kota Tangerang, Banten. Source.

In Jakarta city, social sanctions such as cleaning public facilities have become commonplace. Offenders are forced to don bright orange vests with the words ‘pelanggar PSBB’ (“PSBB violator”) stitched across their backs, before carrying out the punishment. They have two options: sweep the streets or pay the Rp 100,000 fine (USD6.80). The Jakarta authorities reported a ‘drastic decrease’ (“menurun drastis”) in the number of offences committed since the social sanctions were introduced.

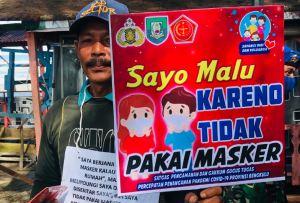

Figure 2: The sign reads, “I am ashamed because I didn’t wear a mask” while the placard says, “I promise to wear a mask when I leave the house. Masks protect me and the people around me. I’m not wearing a face mask; I could be infected with Covid-19”. Source.

Other provinces have followed suit with some variation. Authorities in Kota Bandung, West Java, made offenders do push ups in public. Meanwhile, repeat offenders in Sidoarjo, East Java, are forced to participate in community work, which extended to helping bury the deceased victims of Covid-19. In Bengkulu, people caught for not wearing masks in public have to walk the streets wearing placards and carrying signs promising their repentance. Their pictures were then uploaded on social media to achieve maximum shaming effect.

Tapping on superstitious beliefs

Regional leaders have harnessed the fear of the supernatural in a bid to scare residents into obedience. In Sragen regency, Central Java, a dilapidated sugar factory rumoured to be a haunted house has been repurposed as a quarantine facility. Recalcitrant villagers who refused to self-isolate will be housed in said facility for their 14-day quarantine stay. Residents reportedly avoid walking past the house and shun association with its former ‘prisoners’. Meanwhile, youth volunteers in Kepuh Village dressed as ghosts post-curfew to scare residents off the streets.

Figure 3: The local Covid-19 Response Acceleration Task Force posing in front of said repurposed haunted house in Sragen Regency. Source.

Community Policing

Informal enforcement of Covid-19 prevention measures has been particularly significant at lower levels of government administration. Although the Indonesian military and the national police have been formally tasked with enforcing these rules, their reach and authority in the more peripheral districts are limited. Moreover, their only means of enforcement is issuing sanctions, which is a blunt tool that only deepens public dislike towards the authorities. Softer measures have thus been adopted.

In Indonesia, neighbourhoods within urban and rural villages (kelurahan and desa respectively) are divided into Neighbourhood Units (“Rukun Tetangga”)(“RT”) and Community Units (“Rukun Warga”) (“RW”) for ease of administration. In Jakarta, according to the DKI Jakarta Province Gubernatorial Regulations No. 168 of 2014 (“2014 Regulations”), RTs and RWs are community institutions established by law to aid local governments in carrying out government affairs. They are also tasked with enhancing social cohesion and community empowerment under Article 3 of the 2014 Regulations. According to Article 45, RTs and RWs receive funding from the local government. Its members vote for their leaders. Article 5 stipulates that an RT unit should be made up of between 80 and 160 households. A cluster of a minimum of 8 RTs forms an RW unit. In less populous areas, the figures can be much smaller. The units appear to be rather close-knit; the expectation was that households within RTs and RWs should know each other on an intimate level. In fact, former Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama claimed that these units “should know when children are not in school or when mothers are expecting babies”.

Touted as the ‘Front Guards’ of Covid-19 prevention efforts, RTs and RWs have been entrusted with significant responsibilities in this pandemic. First, they are responsible for identifying vulnerable groups within their communities. Members monitor symptomatic individuals and share updates with the community via specially-developed apps. These community institutions are thus extremely useful as a data-gathering tool for the local government. Each RT and RW also has its own communication platforms for information dissemination and community monitoring purposes. Inhabitants of DKI Jakarta were encouraged to update community Whatsapp groups if they spied any rulebreakers. These community groups are also a key source of information on Covid-19 developments for residents.

Second, RTs and RWs galvanise volunteers to carry out community initiatives. They helm fundraising projects that contribute to pandemic management efforts. Some have assembled teams of volunteers to monitor neighbourhood entryways and traffic in and out of their villages. In Banten Province, local leaders engage in spraying disinfectant from house to house with residents.

Lastly, and most importantly, RTs and RWs have the duty to educate residents on Covid-19 and the mandatory preventive measures. At the initial stages of the pandemic, this entailed inculcating a sense of urgency in the residents. However, social taboos have emerged as the pandemic situation evolved. Many residents resist getting tested due to fears of social ostracising. 10% of traditional market traders within the Tabanan vicinity, Bali, refused to get tested despite being approached by authorities. In the meantime, several areas in Java and Kalimantan have banned funerals for deceased Covid-19 patients, which has strained relationships within the communities. On the other hand, traditional open-air burials persist in several parts of Bali despite fears of potential viral spread. Communities now face the daunting task of alleviating the social stigma surrounding Covid-19. This will require careful calibration as social stigma is a double-edged blade that has also strengthened compliance with social-distancing rules.

Advantages and disadvantages

Indonesia’s community-based approach cleverly taps into existing local traditions and infrastructures to encourage greater compliance with social-distancing rules. It has also freed up more resources for enforcement as villages see more members stepping up as volunteers. This approach covers gaps where the country’s formal resources are simply insufficient to police Covid-19 preventive efforts. This could be one of the reasons why peripheral provinces – where communities play a far more significant role in everyday life – continue to record fewer Covid-19 cases as compared to a metropolis like DKI Jakarta.

Ever since Indonesia lifted large-scale social restrictions in early June, the country has charted unprecedented numbers of new cases. Indonesia has averaged 1700 new cases per day in the first two weeks of July as compared to slightly under 1000 cases daily back in the first week of June. These figures have steadily risen to an average of at least 4000 cases clocked daily since the beginning of October, with a new daily high of 5282 cases recorded as of 25 Nov 2020. What exactly has chipped away at the effectiveness of this community-based approach?

There are at least three factors that have undermined the community-based approach. The first factor is that a significant number of local leaders have merely paid lip service. The issue is not simply one of passive or lax enforcement. Rather, local authority figures themselves have not been faithfully abiding by the regulations. Regents in Riau and North Sulawesi were reported to have engaged in religious activities at mosques back in April and May despite then-regulations banning congregations in places of worship. In Aceh, mass daily prayers continue to take place at mosques without any social distancing. This issue is compounded by contradictory instructions issued by officials within the central authority itself. For instance, on 11 May 2020, the Deputy Religious Affairs Minister reportedly proclaimed that places of worship could operate if they followed health protocol. This directly refuted President Joko Widodo’s instruction for people to worship at home. The inconsistent and contradictory messages from the authorities has been confounded many people.

Another issue is corruption. Local authorities have been accused of usurping resources distributed by the central government. An RT leader in Tangerang, Banten, was put under investigation for allegedly stealing social assistance funds, which he claimed were ‘cigarette money’ (“uang rokok”) acquired via lawful means. Meanwhile, Ombudsman Indonesia had reportedly received over 800 complaints alleging mismanagement of social aid within a month of availing its services online. The fact that these complaints originated from various provinces across Indonesia further underlines the pervasiveness of this problem.

The last factor is more straightforward. Some communities are simply not as closely-knit. In densely populated DKI Jakarta, the size of RTs can go up to 160 families. Community leaders, who usually hold other full-time positions, may be too preoccupied to engage on a more personal level with residents. When a rule requiring community leaders in DKI Jakarta to report on their neighbourhoods thrice a day was introduced, many leaders protested that it was too burdensome. This is a structural problem intrinsic to the grassroots system in Indonesia, that has only come to public scrutiny during the Covid-19 crisis.

While the community-based approach certainly has its merits, it has transformed somewhat into a victim of its own success. The way forward would be arduous; checks and balances should be imposed on the community leadership to ensure that leaders are carrying out their roles as they should be.