Song Yihang

National University of Singapore

Faculty of Law

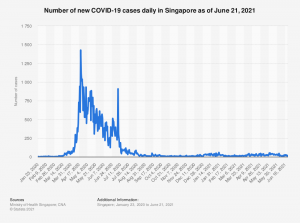

Since the onset of this pandemic, migrant workers have accounted for almost 90% of the over 60,000 cases confirmed in Singapore. The first wave of cases in early 2020 caused the government to put all dormitories on “lockdown” – restricting the movement of nearly 300,000 workers. This eventually extended to the Circuit Breaker – a stay-at-home order and cordon sanitaire that lasted for nearly 2 months.

At the time, a “humanitarian disaster”[1] in the migrant worker dormitories (“dormitories”) seemed likely, with massive infection clusters emerging one after another. Fortunately, with only 27 deaths recorded from the enormous dormitory population, the island-state can be said to have suppressed its mortality rates with a notable degree of success.

However, this close shave with disaster exposed a myriad of challenges faced by migrant workers, which range from alleged discrimination to exploitative employers. In particular, two issues have been brought to the fore as subjects of intense debate, both in the Parliament and by the society-at-large.

First, the urgent need to improve living conditions of the dormitories.

Second, the enactment of laws that segregate migrant workers in dormitories from the wider community.

(1) Living Conditions in the Dormitories

A construction worksite in Singapore typically has hundreds of workers hailing from multiple dormitories at one time. Once an infected worker spreads the virus to their co-workers at the work site, the latter can in turn bring the infection back to their residence or other congregations. These were conditions that directly resulted in the rapid formation of large dormitory clusters in the initial stage of the pandemic.

During the Circuit Breaker, the risk of COVID-19 transmission was further amplified as many migrant workers continued to be housed in crowded and unsanitary dormitories, with up to 20 people sharing a room and communal facilities.

Government’s initial reluctance to review dormitory conditions

When urged by Members of Parliament to review the living conditions in May of 2020, the Ministry of Manpower (“MOM”) acknowledged that the dormitories “could have been upkept better”, but declined to make any additional promises or assurances of rectifications in the interim.

Three primary reasons were cited for the government’s initial circumspection.

First, MOM was concerned about balancing cost considerations when imposing any improvement of living standards on dormitory operators.

According to Minister Josephine Teo, “[i]t is not so difficult for MOM, by the stroke of a pen, to change some numbers here and there. But we have to consider the overall implications and whether it is bearable for the employers.” Whenever the Ministry attempts to demand any major upgrades or enhancements, employers would supposedly “yelp” from the associated increase in housing costs.

This is seen as a countervailing policy consideration, as these costs are said to pass on downstream to the consumers, instead of being borne by the dormitory operators or employers. However, no statistical substantiation has been provided by the government thus far.

Second, there are pre-existing legislations that were deemed sufficient for upholding the living standards in dormitories. The Foreign Employee Dormitory Act (“FEDA”) has been enacted since 2015 and requires licensed dormitory operators to provide, inter alia, common recreational facilities and health infrastructure such as sick bay and isolation rooms. In fact, the government had considered the possibility of a virus outbreak and required FEDA-licensed dormitory operators to draw up and review their contingency plans for quarantine arrangements. Unfortunately, the preparations were insufficient on hindsight, as “no one was quite thinking of something of the scale of COVID-19.”

Enforcement of the FEDA can be seen as a two-pronged approach. First, MOM officers regularly inspect licensed dormitories to ensure compliance with all prescribed requirements. Second, dormitory operators found in contravention of the FEDA may have their licence revoked, be fined up to $50,000 and/or jailed for up to 12 months.

Although the FEDA only applied to dormitories that accommodate at least 1,000 workers, MOM was of the opinion that smaller accommodation types were similarly bound by other applicable guidelines, such as the Building and Construction Authority’s (“BCA”) standards for building structural safety and the National Environmental Agency’s (“NEA”) rules on sanitary facilities. Therefore, the government saw no urgency to supplement any existing gaps in the regulation of dormitories.

Finally, the government’s absolute priority during the Circuit Breaker was to bring the outbreak under control and to resume normality. In response to calls for the government to inquire into the cause of dormitory outbreaks, Minister Lawrence Wong – co-head of Singapore’s Multi-Ministry Taskforce – described the nation as being “in the heat of battle”, and that they should “look back and learn from the experience” only after emerging safely from the crisis.

All dormitories to be regulated under the FEDA

As the COVID-19 cases in Singapore gradually tapered entering 2021, MOM decided to expand the FEDA to encompass all dormitories, regardless of their capacity. Although 60% of migrant workers living in dormitories already reside in FEDA-licensed facilities, further extending the legislation would benefit the remaining 100,000 workers.

After containing the outbreak for a year, the government finally saw the imperative to make such legislative amendments due to a lacuna in the law.

In non-FEDA-licensed dormitories, the government had to rely on the COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Control Order) Regulations to enforce spontaneous but vital requirements, such as creating more isolation bed facilities and imposing stringent infection control measures.[2] However, the COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) Act is a time-limited, “makeshift” legislation that will be repealed after the current pandemic.[3] If FEDA continues to be exclusively limited to large-scale facilities, the government may lack the necessary legal basis to impose similar containment measures across all dormitories in the event of a future outbreak.

This rationale was implicitly recognized by Second Minister for Manpower Tan See Leng, who pointed out that there was a need to “strengthen regulatory levers” and enable the government to “raise and enforce housing standards very quickly across various dormitory types and sizes, and to introduce new housing standards to make dormitory living more resilient to public health risks”.

Lingering problems to be resolved

While the unification of all dormitories under the FEDA is certainly a positive step towards improving the living condition and safety of migrant workers, it is far from a panacea.

For example, even some Factory Converted Dormitories (“FCDs”) – a type of accommodation that is already regulated by the FEDA – are plagued by serious hygiene-related issues. During the 2021 Committee of Supply, it was revealed that stray animals were found to freely roam in certain FCD kitchens, in addition to unclean food preparation and disposal areas.

An additional concern is that the cost of implementing new MOM specifications would be financially devastating for certain employers. This is especially the case for Small, Medium Enterprises (“SMEs”) that are disproportionately affected by the recent economic downturn, and are unable to absorb cost hikes.[4]

Nevertheless, MOM has sought to ameliorate such concerns. Aside from negotiating and engaging various stakeholders,[5] the government has been moving migrant workers into new Quick Built Dormitories (“QBDs”), which are seen as the better and less expensive alternative to the existing Purpose-Built Dormitories (“PBDs”).

Under the traditional PBD-model, private dormitory operators are required to tender for a plot of land for an extensive lease period (e.g. a decade) before constructing the dormitory. This results in two major drawbacks.

First, the sunk cost is extremely high as the operator bears the cost of building the facility. Second, operators may face unpredictable and fluctuating demand for bed spaces over the dormitory’s long lease period,[6] thereby reducing the revenue obtained.

Therefore, operators under the PBD-model would be eager to recover its hefty investment as quickly as possible by overcharging employers during the initial years of the dormitory’s operation.

On the other hand, under the new QBD-model, a “Build-and-Lease” approach is adopted. JTC Corporation (“JTC”) – the government agency that champions sustainable industrial development in Singapore – constructs the dorms based on improved specifications, before leasing them to private dormitory operators. Aside from basic amenities, QBDs come fully-equipped with welfare facilities such as remittance services, barbershops and gyms. Therefore, the QBDs do not require much (if any) investment from the operators, thereby reducing the need for them to levy exorbitant prices on the employers.

Alternatively, it has been suggested for JTC to reassume the role of managing or operating certain dormitories.

JTC possesses the requisite expertise for this role as prior to the privatisation of dormitories, it was the sole entity responsible for providing low-cost accommodation to migrant workers. Therefore, if JTC picks up the mantle as a state-run dormitory operator once again, it could offer healthy competition for the private sector and potentially reduce the housing expenses of SME-employers in the long run.

(2) Confinement of Migrant Workers in Dormitories for Significant Period of Time

During the Circuit Breaker, one of the key factors for lifting the nationwide lockdown was for infections in the dormitories to be reduced. Otherwise, there would always be a risk of “spill over” cases from the dormitory clusters into the wider community.

To minimise this risk, the government pushed the brakes on the movement of workers in and out of all dormitories, and placed those living outside on a compulsory stay-home requirement. Employers and dormitory operators are required to submit an Essential Errands Form before allowing their workers to enter the community.

From 2 June 2020, the Employment of Foreign Manpower (Work Passes) Regulations (“the Regulations”) were amended to require migrant workers (holding Work Permit and S Passes) to be confined in their dormitories. Pursuant to the amended Regulations, workers may only leave their accommodation with their employers’ ‘consent’ in two exhaustive situations:[7]

- When they have permission from the Controller of Work Passes to do so; or

- When they are seeking medical treatment or help in an emergency, or is required by lawful authority to evacuate the dormitory.

However, even as the levels of infection in dormitories diminished entering 2021, the stringent control measures have remained relatively unchanged. Migrant workers continue to be segregated from the wider community, despite being one of the most regularly tested population in Singapore.[8]

Controversy surrounding the amended Regulations

In a joint statement by the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (“HOME”) and Transient Workers Count Too (“TWC2”), the two local migrant welfare groups heavily criticised the amended Regulations. In their opinion, as Singapore exits the Circuit Breaker, “the draconian measures to contain and control COVID-19 among migrant workers should likewise be minimised – not entrenched in even more sweeping and harsh laws.”

Their concerns may be summarised in the following two points.

First, the amended Regulations have the potential of conferring employers with unfettered power over the migrant workers’ ability to leave the dormitories. The Regulations neither list any objective criteria for what warrants “medical treatment”, nor does it explain what constitutes an “emergency”. As a result, if an employer exercises their discretion to disallow a worker from leaving the dormitory, there appears to be no immediate recourse for the latter under the law. According to HOME and TWC2, such a formulation “offers no scope for workers to leave their accommodation to seek redress, case advice or new jobs.”

While disenfranchised workers technically retain legal recourse in judicial review on grounds of illegality[9] or irrationality[10], this remains somewhat of a unicorn if they are unable to leave the dormitory to begin with – let alone to seek legal advice.

Second, the Regulations are not time-limited, unlike the COVID‑19 (Temporary Measures) Act which contains a sunset clause that ensures the temporary-nature of any restrictions imposed thereunder. From the perspective of these migrant welfare groups, the government’s decision to introduce such measures via the Regulations instead of the COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Control Order) Regulations “symptomises their discriminatory and prejudicial nature”.

Government’s justifications for maintaining restrictive measures on dormitory-community interactions

Although the government has yet to directly respond to the abovementioned concerns, their stance on the matter may be gleamed from ministerial statements in parliament. Their justifications for confining migrant workers in dormitories may be summarised in the following points.

First, the government is adamant to err on the side of caution, to prevent further clusters from developing in the dormitories. This was said to not only be in the community’s interest, but

also protects the migrant workers’ livelihoods, as a second Circuit Breaker would be devastating to industries that rely on their services. This outcome may be inferred from the recent implementation of Phase 2 (Heightened Alert) measures following a second wave of cases in the community, where the construction sector suffered greatly from “reduced productivity due to safe management measures at the work sites”.

Second, the government attempted to draw the public’s attention to efforts that have already been made to provide welfare within the dormitories. Hardware such as WiFi access and SIM cards have been provided free-of-charge to the workers, and certain communal facilities have resumed operations within the dormitories. By March 2021, workers were allowed to visit Recreation Centres up to 3 times a week, with each visit being up to 4 hours long. In addition, there are plans to allow certain workers to visit the community once a month.

In light of the more virulent strains of COVID-19 spreading in the community, it may have been fortunate on hindsight that the government chose to ease restrictions on dormitories in a relatively controlled manner. With the ongoing second wave in the community, the prospect of significantly liberalising dormitory-community interactions seems remote, at least for the immediate future.

Conclusion

The pandemic has elevated migrant workers from a forgotten segment of society to a focal point of public discourse. Due to the spotlight, many blunders observed at the early phase of the crisis have been or are gradually being improved. For example, the initial failure at containing dormitory clusters exposed the plight of migrant workers, and eventually compelled the government to make essential legal and institutional reforms. As inoculation rates in the dormitories continue to increase, MOM has expressed hopes of progressively easing restrictions for migrant workers. Moving ahead, there remains to be ample room for the living conditions and laws regulating dormitories to be enhanced, such that the welfare and safety of migrant workers can be adequately protected in the future.

[1] As described by NMP Associate Professor Walter Theseira during the Ministerial Statements in Parliament, on 4 June 2020: <https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/sprs3topic?reportid=ministerial-statement-1402>.

[2] Under new MOM specifications, dormitories will have no more than 10 beds per room, with only single-deck beds and 1 meter spacing between them: <https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-releases/2020/0601-joint-mnd-mom-media-release-on-new-dormitories-with-improved-standards-for-migrant-workers>.

[3] The COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) Act was initially valid for only 6 months from 7 April 2020, with the Minister of Law given power to extend it up to one year. Thereafter, further extensions can only be warranted/authorised by the Parliament: <https://www.mlaw.gov.sg/news/parliamentary-speeches/second-reading-speech-by-minister-for-law-mr-k-shanmugam-on-the-covid-19-temporary-measures-bill>.

[4] This was pointed out by MP Cheng Li Hui during the 2021 Committee of Supply: <https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/sprs3topic?reportid=budget-1608>.

[5] MOM is currently doing so, as part of the review process on expanding the scope of FEDA. More details on the amendments will be provided in the fourth quarter of 2021: <https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/sprs3topic?reportid=budget-1612>.

[6] For example, due to tightening of foreign labour rules or other government regulations.

[7] See paragraph 2C, Part III to Fourth Schedule of the Regulations.

[8] Routine tests are conducted on dormitory residents every fortnight, including workers who have recovered from COVID-19: <https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/covid-19-tests-dormitories-worksites-cluster-cases-westlite-14710028>

[9] For example, the employer must not take into account wholly irrelevant or extraneous considerations in exercising their discretion: Lines International Holding (S) Pte Ltd v Singapore Tourist Promotion Board and another [1997] 1 SLR(R) 52. The worker may also challenge the employer’s determination on the basis that the latter has exercised statutorily conferred power for a purpose unauthorised and unintended by Parliament: R v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, ex parte World Development Movement [1995] 1 WLR 386.

[10] The worker may potentially challenge the employer’s determination on the basis of Wednesbury unreasonableness.