Jeong Do Gi

National University of Singapore

Faculty of Law

Throughout the unfolding of the COVID-19 pandemic, South Korea has garnered international praise for the way it has addressed the pandemic. Due to this perceived success, even foreign leaders of state such as the French President and the Swedish Prime Minister have reached out to President Moon Jae-In to inquire as to how such success may be replicated in their own countries.

However, beyond the effectiveness of South Korea’s infection prevention strategy in maintaining relatively low numbers, it is also of particular interest how the government has managed to implement relatively aggressive measures whilst mitigating public backlash and non-compliance.

The emphasis of South Korea’s approach lay on aggressively fighting the virus through widespread testing and the use of technology in order to allow for the economy to continue running and to minimally restrict movement and assembly for the general public (i.e. not going into lockdown). Thankfully for South Korea, extensive laws and systems had already been put into place following the previous MERS-CoV pandemic in 2015. Most notably, the Infectious Diseases Control and Prevention Act (IDCPA; 감염병의 예방 및 관리에 관한 법률) and the Quarantine Act (검역법).

‘Soft’ lockdown and social distancing

It is important to note that South Korea has completely avoided legally enforcing any social distancing measures or even a lockdown amongst the general public. Such precautions have only been put forward as strong recommendations. Legal measures have mainly focused on utilizing local governments to place administrative orders on businesses, assemblies and religious facilities where they do not abide by quarantine measures.

It is important to note that South Korea has completely avoided legally enforcing any social distancing measures or even a lockdown amongst the general public. Such precautions have only been put forward as strong recommendations. Legal measures have mainly focused on utilizing local governments to place administrative orders on businesses, assemblies and religious facilities where they do not abide by quarantine measures.

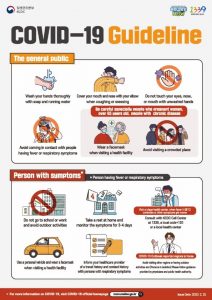

The government thus introduced the concept of “Distancing in Daily Life", put forward as a new, sustainable way of life to prepare society against the possibility of long-run prevalence of COVID-19. It was designed to achieve the goal of infection prevention and containment while sustaining people's everyday life, economic, and social activities.

The social distancing in daily life scheme consists of 5 key rules: stay home for 3-4 days if you feel unwell; keep a distance of 2 arms' length from others; wash your hands for 30 seconds and cough or sneeze into your sleeve; ventilate at least twice a day and disinfect regularly; and, stay connected while physically distancing.

Further, recently in November, South Korea replaced the previous three-tiered social distancing scheme with a more specific five-level system in order to mitigate the impact on the economy and small businesses. These levels are – 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5 and 3. For example, under the previous system, night clubs would be required to fully close under Level 2, but with the new Level 1.5, clubs may stay open and resume business, but patrons are not allowed to dance within the venue.

Extensive Testing and Tracking

If South Korea is one of the few countries that has a hardline approach to avoiding a lockdown, this has been balanced by strong mask adoption, stringent quarantine measures and extensive testing and tracking.

Although South Korea had already seen very high percentages of face mask adoption within the general public, beginning early November a legislative mandate for mask wearing had been introduced. This makes mask wearing mandatory for 23 different classes of venues, such as public transport, internet cafes, clubs, and department stores. People caught in breach of the regulations will face a fine of up to 100,000 won (~USD$90). Operators of those facilities will face fines of up to 3 million won for failing to ensure that users comply with such requirements.

Within two weeks of the country’s first case, South Korea had already shipped out thousands of test kits and by late February had tested over 60,000 people, compared to the U.S which had only by then tested just over 400. As of the most recent figures, South Korea has quite remarkably tested over 3.5 million individuals. Beyond this, South Korea had managed to set up over 550 screening clinics in the first three weeks, and implemented innovative testing strategies such as drive-in testing sites and “phone booths” which separated medical professionals from patients on either side of a glass panel affixed with rubber gloves

Beyond extensive testing, the government has utilised advanced tracking technology to collect important personal data to achieve detailed contact-tracing. This process is hastened by the exception laid out in Article 76-2 of the IDCPA which provides the Minister of Health the authority to collect personal data, without a warrant, from both confirmed and potential patients for public interest purposes.

Confirmed COVID-19 cases (blue) and pharmacies with face masks available (yellow) (Image: Government of Korea)

With access to such extensive data, the Infectious Diseases Control and Prevention Act (“IDCPA”) further requires the Minister of Health to maintain utmost transparency with citizens. Article 34-2 of the IDCPA states that the Minister of Health shall “promptly disclose information with which citizens are required to be acquainted for preventing the infectious disease, such as the movement paths, transportation means, medical treatment institutions, and contacts of patients of the infectious diseases”. Local authorities have thus been active in sending out ‘emergency alerts’ to people’s smartphones to notify them of the discovery of each infected individual in the area. This includes information regarding where each person has been and for how long so that citizens may make informed decisions as to whether to get tested.

However, in the obtaining of such personal information, the government is required to comply with strict requirements imposed by the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA; 개인정보 보호법), the general data protection legislation in South Korea. Some general principles include that a personal information controller must explicitly state the purposes for which the personal information is to be processed and must collect such information as is minimally necessary for such purposes, not using it beyond such purposes. Further, such data is required to be deleted after being utilised for the purposes it was collected.

Pursuant to these statutes, the South Korean government has created an extensive public database which simulates a clear track of the past movements of infected individuals - utilising information from their credit card transactions, mobile phone signal data and CCTV footage. No names or addresses are provided, however, the information is sometimes substantial enough for patients to be identified. Consequently, certain patients have been the centre of online judgement and ridicule. For example, a 46-year-old woman from Cheonan, who tested positive for the virus on 27 February, drew online criticism as her travel history revealed that she was a member of a controversial religious group known as Jesus Morning Star.

In light of such leaks, the Korea Communications Commission (KCC) has made it clear that the disclosure of personal information of patients, other than by relevant quarantine authorities is illegal and may be subject to civil and criminal penalties. For example, four civil servants working at the Seongbuk District Office in Seoul were arrested for leaking a confirmed patient’s information in a messaging group chat such as whom they had met over the Chinese New Year holiday.

The future ahead

Overall, South Korea has been able to tackle this pandemic with aggressive testing and tracking methodologies whilst maintaining a high responsiveness to public concern. This has allowed the Moon administration to garner public compliance. However, amidst rising cases nearing the end of the year, it will be interesting to see whether the public begins to display fatigue or remains as supportive towards tightened restrictions after months of more relaxed measures.