Faye-Anne Ho

National University of Singapore

Faculty of Law

The Experts behind the "Japan Model"

Compared to many other countries around the world, Japan has appeared rather relaxed in its response to the spread of the coronavirus within its borders. Probably best known as one of the few countries which did not impose a lockdown during the pandemic, the Japanese Government’s approach saw a focus on social distancing measures, while conducting relatively low numbers of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests used to detect the virus in individuals. Its unique contact tracing approach of primarily identifying the sources of cluster infections also strongly characterises what some now refer to as the “Japanese Model” to tackling the coronavirus.

Underlying this unique response was the “cluster-based approach” [クラスター対策] to controlling the spread of infections – formulated and driven by Japan’s Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting [新型コロナウイルス感染症対策専門家会議]. Consisting of key experts in Japan ranging from researchers at the Japanese National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID) to university professors in the public health and medical fields, this twelve-member panel was set up by Japan’s national taskforce to provide advice on the government’s coronavirus countermeasures from a medical point of view.

Read more

The cluster-based approach

The Expert Meeting’s approach all began with a study of the coronavirus outbreak aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship, which docked at the Yokohama Port in early February 2020. Conducted by the NIID, the study observed the formation of clusters of infections to be a key reason behind the outbreak aboard the quarantined ship. Research data also revealed certain types of settings and individuals that were more prone to becoming sources of cluster infections.

In reliance on this study, the Expert Meeting had proposed the early detection and response to clusters as one of the key strategies the government should take in response to the coronavirus. This involves both the quick containment of existing clusters and the prevention of more clusters from forming, in order to reduce the chances of a large-scale outbreak of infections arising from clusters. This was also crucial in order to avoid overwhelming Japan’s medical system, which already suffered from a shortage of resources such as hospital beds.

Marking a shift from the Japanese Government’s initial focus on the containment of imported cases, this approach has largely formed the basis of the government’s basic policies, which seek to balance infection prevention measures with the maintenance of socio-economic activities.

Guiding the Japanese style of social distancing

First, the NIID’s findings based on the clusters of infections aboard the ship showed that clusters tend to form more easily in enclosed spaces, crowded settings or where there is close contact between individuals. This led to the formulation of the “3Cs” (closed spaces, crowded place and close-contact settings) by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) – a simple and easy-to-remember guideline familiar to most Japanese by now.

With a constitution that strongly protects civil rights and affords the government little power to enforce orders or impose restrictions on society, Japan was one of few nations which did not enforce any lockdown nor hard restraints on daily activities. Such social distancing guidelines were hence particularly important for Japan, in ensuring its goal of continuing socio-economic activities while curbing the virus – so long as the 3Cs were avoided in doing so.

In fact, the 3Cs have also guided the PCR testing regime for some local governments. Prefectures such as Saitama and Tokyo have gradually carried out more rigorous testing in bars and clubs – which were identified as areas where the 3Cs are usually observed and hence more likely to become a breeding ground for clusters to form. Indeed, recent statistics reveal clusters emerging in areas such as Shinjuku, where nightlife is more prevalent.

Expert studies have also found their way into other public guidelines released by the MHLW. The “10 tips to reduce person-to-person contact by 80%” was another notable social distancing guideline based on the research by Professor Nishiura Hiroshi from the Cluster Response Team, which encouraged citizens to carry out activities remotely or in small groups where possible to slow the spread of the virus.

Retrospective contact tracing

The cluster-based approach was also instrumental in developing Japan’s contact tracing methodology. A key observation made in the NIID’s study was that many passengers on the cruise ship were not infected despite coming into close contact with infected persons. Instead, the research suggested that clusters were formed by certain infected individuals, who have a greater tendency to transmit the virus to more people than others.

The focus of Japan’s contact tracing efforts was hence to prioritise the quick containment of such infected individuals – by identifying common sources of infection among the existing COVID-19 cases identified. In other words, contact tracing in Japan looks retrospectively to track down and isolate the original source of infection which led to a cluster of cases detected, rather than identifying new cases based on the close contacts of the infected persons.

It hence focuses more on pinpoint testing in the identification of clusters, rather than a broad testing of the population. Still, some also suggest that the low PCR testing numbers were merely due to the lack of resources available and poor government funding, rather than a part of the government’s strategy to contain the virus.

This approach to contact tracing had been adopted in Hokkaido during its prefectural state of emergency in February – where a cluster of Chinese tourists were identified and swiftly contained. The perceived success of Hokkaido’s state of emergency can be said to have demonstrated the effectiveness of the cluster-based approach to contact tracing, influencing its adoption by the Cluster Response Team [クラスター対策班] established within the MHLW later on.

The actual contact tracing exercise was conducted at Japan’s 469 local public health centres, where analogue contact tracing methods such as interviewing confirmed cases on their recent activities and whereabouts were carried out to determine the sources of infection. Meanwhile, the MHLW would facilitate these efforts and centralise the data collected in order to track the outbreak of clusters in the various regions of Japan.

Of course, this does not mean that Japan has not made any efforts in prospective contact tracing. Aside from the contact tracing efforts by the public health centers nationwide, local governments of prefectures such as Hokkaido and Osaka have initiated their own contact tracing systems to record the basic information of event attendees or people entering and leaving various facilities. The Japanese Government also released the contact-tracing app “COCOA” in June, which uses Bluetooth technology to inform users if they have come into contact with someone tested positive for the virus. The effectiveness of the app is yet to be seen, however, with only 3 confirmed cases having logged the details of their diagnosis on the app as of July 8.

Avoiding hospital clusters

Another focus of the cluster-based approach was the prevention of the clusters forming at hospitals – an unconventional measure compared to many other countries which focused more on other common “breeding grounds” for clusters such as schools and public facilities.

For example, vulnerable individuals with a higher risk of infection, such as the elderly and patients with pre-existing conditions, were advised to seek treatment remotely where possible. This would avoid such individuals forming part of a cluster at medical institutions where infected patients would visit for treatment.

In addition, based on an observation of milder COVID-19 cases aboard the cruise ship made during the NIID’s study, the Japanese Government made the rather controversial decision of requesting people with lighter symptoms of the virus to recuperate at home, instead of seeking medical attention at clinics or hospitals.

The concern was that people with lighter symptoms would spread the virus to other uninfected patients visiting the hospital for other purposes, thereby forming further clusters of infections. Of course, such measures would also help to lighten the burden on Japan’s strained medical system.

Public reception

The experts’ cluster-based approach has seen regulatory consequences in the form of low PCR testing rates and social distancing guidelines, which characterise Japan’s unorthodox response. Yet, these very features have also been subject to concern and criticism from citizens, reflected in the drop in approval ratings for Prime Minister Abe’s administration.

Indeed, in proposing a path less taken by countries in responding to the spread of the coronavirus, the Expert Meeting clearly faces difficulty in convincing the nation to comply with its unconventional and sometimes radical policies. One of the biggest concerns expressed was regarding the unsettlingly low PCR testing rates. With some lacking a clear understanding of the technicalities behind Japan’s cluster-based approach, many citizens criticised the high testing standards imposed by the government. Others feared the possibility of hidden cases within the country that could arise from the lack of testing and the strict standards for testing imposed under the approach – pointing out that it risks leaving asymptomatic cases undetected and hence free to form clusters.

The anxiety was further heightened by reports that even people with more severe symptoms like fever were denied testing due to the overworked public health centres during the influx of suspect cases. The slowing down of operations at these facilities also raised concerns over the feasibility of the cluster-based approach in contact tracing, which is said to work best at the initial stages where there are a few infected persons and an early detection of clusters.

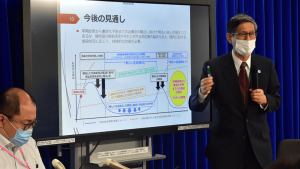

An accumulation of the anxiety and doubt expressed by the public could have possibly led to the disbandment of the Expert Meeting on June 24. A new panel was formed as a subcommittee under the national taskforce [新型コロナウイルス感染症対策分科会] instead, which included local government officials and crisis management experts in addition to 8 infectious diseases experts from the original Expert Meeting. It was explained that this reorganisation would allow the experts to have a legal backing under the national taskforce, addressing concerns raised over the original expert meeting being perceived as having full control over the government’s countermeasures, despite not constituting a legal body.

Reflecting on Japan’s cluster-based approach

Japan has definitely come a long way since the outbreak of the virus aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship – the first major cluster to be detected within its borders. While managing to avoid a huge outbreak of infections and placing a burden on its medical system, Japan has also seen one of the lowest death rates around the world from COVID-19.

The country’s relative success in suppressing an outbreak of infections, however, is met with growing public disapproval at the countermeasures that were taken. To a certain extent, this likely stems from existing public mistrust towards the Japanese Government. Speculations at to the relationship between the experts and the government could have led to the loss of credibility of these experts and the countermeasures they proposed. In this aspect, more transparency and clearer communication from the experts and government officials to the Japanese people may help to build trust and improve this relationship.

The public’s concern over the effectiveness or suitability of the government’s measures could also have been a fault of the cluster-based approach itself. Issues such as the overworked public health centres during the peak in infections have shown that the approach is not a perfect solution to overcoming the virus in Japan. Considerable public anxiety was also expressed regarding the focus on clusters, which does inevitably overlook other more minor cases of transmission that still ultimately lead to an increase in infections. With the coronavirus still a relatively new and unfamiliar disease, many perceived the government’s measures under the approach as insufficient and lacking thoroughness. Such anxieties and doubts as to the effectiveness of the approach may only continue to grow should the number of infections start to increase again.

The key challenge of continuing with this cluster-based approach is hence in seeing that such measures are sufficient to help Japan successfully overcome this crisis, but at the cost of the gaps in the approach and public mistrust. At the moment, such “counter-cluster” measures remain a key policy of the Japanese Government as it continues to deal with the spread of the virus in Japan.

Thus far, Japan has seen itself through a second wave of infections centering around the capital city of Tokyo, where significant efforts were taken to conduct mass testing on various groups within the community. The exponential increase in daily PCR tests conducted across Japan as its major cities experienced a resurgence of cases reflects the increased political pressure on the government to step up on prospective contact tracing – both to quell public anxiety and in recognition of a need for the early detection of clusters. Indeed, the cluster-based approach may be in need of some re-shaping to tackle future outbreaks of infections, as both the experts and the public continue to learn about the virus. With the country undergoing a recent change in leadership, the national taskforce has also begun operations under a new expert panel, which has since released its own set of cluster-prevention guidelines to facilitate Japan’s lifting of the state of emergency. It remains to be seen how the new panel’s implementation of this cluster-based approach will be received by the public, as Tokyo recovers from its second wave of infections, and the government pushes for the gradual resumption of socio-economic activities.

Handling an epidemic without emergency powers

While the COVID-19 pandemic has forced governments around the world to shut down entire countries, people in Japan continued to roam the streets, with shops and public transportation across the country remaining in operation.

As one of the few countries which did not undergo a “lockdown”, the Japanese Government’s goal of sustaining socio-economic activities while curbing the virus may appear an ambitious and unrealistic goal to many societies. Yet, Japan has also caught widespread attention for its results in both handling infections and ensuring compliance with its preventive measures, as it observed its first wave of infections across the country earlier this year.

Source: https://www.fashionsnap.com/article/corona-photo-report/

Read more

Legal Measures taken

A key reason behind the lack of strong measures taken in Japan lies with their constitution – which grants little power to the government to deal with a national emergency. The Japanese Constitution, which remains unamended since its enactment post-WWII, sees a strong protection of civil rights – with over 30 provisions providing for fundamental liberties and rights to citizens. On the other hand, no provision allows for the government to violate such rights under any circumstances. Put simply, even during an emergency such as the spread of an infectious disease, government authorities in Japan cannot force citizens to act a certain way, nor impose restraints over the citizens – harsh measures normally taken in many other countries to control such situations.

Of course, this does not completely disable Japan’s government from handling an emergency, as there are still ordinary laws to be relied upon. For example, the government’s request for the closure of all schools, as a preventive measure to curb the spread of the coronavirus, was made under Article 20 of Japan’s School Health Safety Act. Indeed, even without much legal powers under the Constitution, the Japanese Government was able to make use of existing legislation instead to manage specific areas, such as border control and quarantine, in response to the epidemic situation.

While the Abe administration had proposed a constitutional amendment to include emergency powers earlier in March 2020, this was promptly met with strong resistance from legal practitioners and opposition party members in the country.

Instead, the government proceeded with the legislative reform of the Act on Special Measures for Pandemic Influenza and New Infectious Diseases Preparedness and Response [新型インフルエンザ等対策特別措置法] (“Special Measures Act”) – enacted in 2012 to tackle the spread of the novel influenza disease.

This Special Measures Act served to clarify the powers of both central and local governments in taking the necessary measures regarding citizens’ lives and the national economy, for the purpose of handling the spread of an infectious disease. The Act contains a list of provisions specifying the actions which government authorities are permitted to take based on an assessment of the situation of infection. For example, under Article 35 of the Act, the central government could declare a state of emergency over designated regions in Japan for a specified period of time – which would allow for strengthened countermeasures to be implemented in those areas. In preventing the spread of the virus, prefectural governments could take countermeasures such as requesting for facilities to close, citizens to refrain from going out, and events to be cancelled under Article 24 of the Act. The provision also empowers these prefectural governments to publicise the names of facilities which refused to comply with requests for closure.

Of course, it should be noted that such powers granted by the Act merely allow government authorities to request for certain actions to be taken, and citizens cannot be forced to comply nor punished for non-compliance. However, such requests arguably seem to carry more weight in the Japanese society, though citizens are ultimately not obliged to comply with them.

Still, the sufficiency of these legal measures alone is questionable. Crowds were observed at many popular tourist spots across the during Japan’s golden week holiday season, despite the government’s request to refrain from going out. Some pachinko parlours in Osaka ignored the governor’s requests for closure, yet received more customers even when their names had later been publicised by the governor. And in February, a few prefectures had initially chosen not to comply with Abe’s sudden request for schools to close, or delay the school closures in their area, due to concerns over the impact on schools and parents on such short notice. With no penalties for the contravention of government orders made under these laws, the proper enforcement of such measures remained a challenge.

Osaka Mayor publicising Pachinko Parlours which did not comply with closure requests

Source: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/04/24/national/osaka-names-pachinko-parlors-epidemic/#.XqTkg8j7Q2w

Targeting a behavioural change with social distancing policies

Instead, the Japanese Government focused on what appeared to be a rather relaxed approach of preventing the spread of the virus simply with social distancing guidelines.

Underlying this was the core idea of effecting a behavioural change in the public, by seeking their cooperation in exercising jishuku, or voluntary self-restraint. This has been repeatedly encouraged by authorities in an aim to ensure effective social distancing, by requesting the public through guidelines to refrain from unessential or unnecessary travel, and from attending gathers or events. Still, the carrying out of usual socio-economic activities remained largely unprohibited under the government’s guidelines.

The key framework adopted was the “New Lifestyle” – a set of guidelines released by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare to lower the risk of infection in all aspects of daily life. This included guidelines for preventing the outbreak of clusters by avoiding the 3Cs (closed spaces, crowded place and close-contact settings), as well as tips for maintaining proper hygiene standards and minimising physical contact with others. Similar general guidelines for preventing infections were also released by the relevant government authorities for specific entities such as schools, workplaces and public facilities.

Enforcing jishuku

Though total compliance with the government’s preventive measures was not enforceable nor achieved in Japan, reasonable signs of public adherence were still observed.

A study based on mobile phone data showed around a 50% decrease in the number of people recorded on the streets, when requests to refrain from going out were made during the state of emergency. Though some difficulties were observed, most schools and workplaces across Japan had remained closed and transitioned to operating remotely. Amusement park closures were also announced, and concerts and fairs were swiftly cancelled in line with the government’s request to refrain from holding large-scale events.

This could be due in part to the actions taken on the ground – such as by local authorities and other organisations – to encourage compliance with the government’s social distancing guidelines and requests.

Indeed, without proper systems of enforcement to regulate compliance with preventive measures across the country, Japan relied heavily on the efforts of local governments to monitor and handle the situation in their respective regions. Local public health centres were central to Japan’s contact tracing efforts, and the respective prefectural governments also acted as consultation centres to answer to citizens’ queries and concerns on the measures taken.

While these local authorities generally acted within the scope of the general guidelines released by the central government, they also had some autonomy to enforce their own policies beyond these instructions, or what they are allowed to do under the Special Measures Act. In monitoring the local infection situation, these authorities adjusted the specific countermeasures implemented within the region, sometimes by declaring a prefectural-equivalent of a state of emergency when the local state of infections worsened – as observed in Hokkaido and Tokyo. Efforts were also made to raise awareness on the virus and the preventive measures to be taken – with government messaging being broadcasted across various media outlets. Some prefectures even had government officers patrolling the streets with signs requesting people to stay at home.

Source: https://mainichi.jp/articles/20200411/k00/00m/040/166000c

These local authorities are hence a key driver of the actual preventive measures taken around Japan. Of course, another notable action was the local governor’s ability to publicise the names of facilities that did not comply with closure requests under the Special Measures Act, in an effort to enforce measures for facility closures. To a certain extent, this also amounts to a form of social shaming – which is possibly more effective in Japanese society given the significance of shame in their culture.

On the other hand, informal efforts were also made to publicly recognise facilities which complied with government requests or took social distancing measures. The Hokkaido government, for example, published on its website a list of businesses named as “model examples” for their efforts in taking infection prevention measures.

Businesses and organisations arguably had a role of aiding the enforcement of government measures as well, via the societal pressure created by the image and influence of such private entities. During the national state of emergency, it was not uncommon for Japanese companies to promptly publish the measures they were taking within the company to ensuring a safe working environment for their workers, in response to the government’s guidelines for workplaces and businesses.

Shops and restaurants also largely endeavoured to create a safer environment for their customers in line with government measures. Clothing brand Uniqlo, for example, was quick to implement social distancing measures at its branches across Japan. Many eateries also began offering take-out or delivery options to accommodate and encourage efforts to stay at home where possible. Various efforts to accommodate and support the community’s compliance with government guidelines under the “New Lifestyle” were observed as well. Family restaurant chain Saizeriya took an innovative approach in undergoing a menu renewal so all food prices end with 00 or 50 yen, in order to reduce the chance of contact by minimising the use of 1, 5 and 10 yen coins.

Some companies also took the extra step of engaging in charity work or community-related initiatives. Apart from donation of money, technology, food and clothing to essential workers in the society, companies also held activities and initiatives to support the community’s Stay Home lifestyle. For example, telecommunications company NTT produced a series of fitness videos created by the group’s corporate sports team and fitness trainers, to encourage citizens to maintain a healthy lifestyle while staying at home. Japanese multinational group Suntory took part in the “Sakimeshi” project (「さきめし」プロジェクト) – an initiative to provide economic support for F&B shops affected by the preventive measures. Such efforts arguably provide a form of social support, in encouraging citizens and providing them the assurance to comply with the government’s request to close facilities or stay at home.

Evaluating Japan’s response

Without the ability to impose any significant restrictions under the restraints of its constitution, the Japanese Government’s attempt to effect a behavioural change in the society through requests and a certain extent of public shaming and pressure has definitely been a unique approach to handling the coronavirus.

An observation of the earlier stages of Japan’s infection situation sees an initial increase in numbers which were eventually brought down during the declaration of the state of emergency, where tightened measures were implemented. With no huge outbreak of infections recorded, Japan has also seen one of the lowest death rates in the world from the coronavirus. Safe to say, Japan has been relatively successful in its control of the spread of the coronavirus in the country.

Several factors have been suggested in explaining Japan’s success, including the quality of their healthcare and medical system, as well as the cluster-based approach formulated by Japanese experts to handling the spread of infections.

But perhaps the more interesting question to be asked is the effectiveness of the government’s social distancing policies in bringing about these results. How much of Japan’s success can be attributed to the government’s soft approach of controlling socio-economic activities with guidelines and requests?

While the failure to ensure a complete enforcement of its soft measures surely illustrates that the Japanese government’s approach was not perfect, as of now, it seems to have been reasonably effective in guiding Japan’s success in containing the coronavirus. Statistics showing a decrease in infection rates, corresponding with the implementation of government measures during the state of emergency, suggest that these policies have worked to some degree.

Enforcing penalty-free measures, especially in a large country like Japan, is definitely no easy feat. Indeed, many have tried to propose possible reasons for the perceived success of this soft approach in Japan’s society. While the public’s response to the government’s measures could be due in part to the fact that they mostly had a legal basis, the success in enforcing such preventive measures may also stem from the ground efforts by smaller stakeholders such as local authorities, organisations and companies. These have arguably acted as an invisible driving force strengthening the effectiveness government’s measures – whether by regulating its enforcement on a deeper level in the respective regions across Japan, or by building up a community spirit to encourage compliance among residents.